Six-second test weeds out fake diamonds

Post Date: 11 Apr 2014 Viewed: 450

At work: but screening techniques are changing

When it comes to spotting synthetic or other fake diamonds, rigorous caution is the industry's modus operandi.

It has good reason to be careful. In May 2012, an unsuspecting diamond merchant bought a parcel of what was believed to be 605 natural diamonds ranging from 0.30 to 0.70 carats.

When the buyer sent a sample to be certified at the International Gemological Institute, tests revealed a number of undisclosed synthetics. On examination of the package, 461 diamonds were verified as synthetic.

Diamonds certified in laboratories are usually a quarter carat or larger and, because of routine testing, relatively few synthetic stones of this size - known as "melee" - are known to have reached consumers without being properly identified. However, in the case of smaller stones - weighing 0.18 carats or less - it often costs more than a stone is worth to have it graded.

It is these smaller stones that represent a risk. Synthetic production methods have become more cost effective in the past few years. Imitations passed off as natural stones remain potentially market-destabilising threats to the integrity of the supply chain, as well as to fragile consumer confidence.

"The issue about undisclosed synthetics is almost exclusively in very small stones like 10 or 12-pointers, or under a quarter of a carat," says Russell Shor, an analyst at GIA, who predicts an increase in undisclosed activity as production becomes faster and cheaper.

Synthetics may enter the supply chain undisclosed through cottage-industry manufacturers mixing a few fakes among natural diamonds, or through the activity of unscrupulous traders at import. Yet it is difficult to pinpoint where risk lies.

"Our understanding is that synthetic diamond production is very small, accounting for less than 500,000 carats per year. This is less than 0.5 per cent of rough diamonds mined per year - around 128m carats, according to Kimberley Process statistics," says De Beers, the diamond company.

The proportion may be small, but De Beers is placing itself at the forefront of detection technology, with the Automated Melee Screening device (AMS).

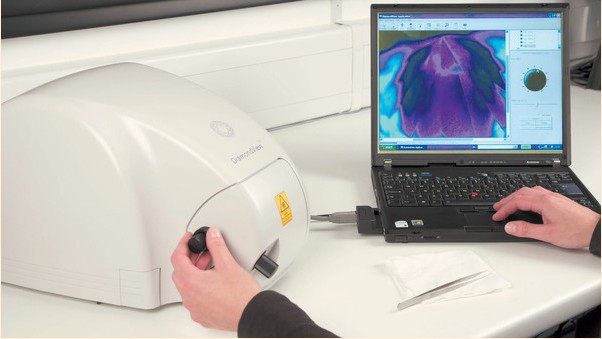

The AMS is designed to provide a natural guarantee for melee stones from 0.01 to 0.20 carats. It was developed following requests from De Beers' rough-diamond clients for automated detection equipment that could be used in volume on small stones.

"We don't view [synthetics] in any way as a threat," says Stephen Lussier, an executive director of De Beers. He adds that the group aims to offer "the ultimate confidence" to clients and their customers through its detection technologies. "It's just preparing to make sure that there are no issues in the future rather than reacting to anything particular of importance today."

The AMS machine will allow thousands of melee stones to be poured into an automated feeding system. Existing methods require a technician to place individual stones in a machine. The AMS screens about 360 stones an hour using a fibre optic probe to verify authenticity or refer stones for further testing.

For some years, De Beers has supplied its clients and larger laboratories with manually operated detection equipment for larger stones. It has gained valuable insights through Element Six, a synthetic industrial diamond supplier that is part of De Beers.

The AMS will be made available from next month. De Beers' priority is to satisfy its own customers' needs, but it is also looking to set up a screening service in important diamond-cutting centres where the need arises.

Taché, a dealer with direct access to its rough diamond suppliers that is part of the De Beers Group, says it does not find synthetics problematic. However, it has leased the AMS to give its clients confidence and reassurance, according to Maurice Zajfen, the company's financial manager.

Mr Lussier says: "In many ways, we're in a hell of a lot better position than something like the art market. Within about six seconds we can tell you whether [a stone is] a natural diamond."

The technological development reinforces the idea that synthetic jewellery is not the real thing, as described by Mr Lussier. The allure and superiority of natural diamonds is at the core of De Beers' brand offering, and explains the premium price that equipment such as the AMS helps to protect.

According to Mr Lussier, cubic zirconia, moissanite and other imitations have not had any real impact on the market "because those who want to buy a diamond are buying for a whole different reason.

"It's about the emotion, the preciousness, the value, the rarity," he says.

Natural examples may command the highest values but, elsewhere in the industry, fully disclosed cultured pearls and coloured synthetic gemstones have found legitimate places in the market.

Mario Ortelli, an analyst at Bernstein Research, speculates that imitation diamonds could follow a similar trend. Changing consumer attitudes would require time and investment, he says: "Marketing spend is very important in the perception."

If a synthetic producer were to create a convincing proposition, De Beers and other jewellers would have to take a strong stance against that message, Mr Ortelli suggests.

"The real threat is more for De Beers than for the jeweller," he adds. Should consumers embrace synthetic diamond jewellery - superficially indistinguishable, but cheaper than natural diamonds - jewellery brands could respond by creating higher margins.

Mr Lussier recognises interest in synthetic stones in markets such as India, but is unconcerned. He says De Beers is unlikely to launch a synthetic diamond arm. "We think the issue isn't one of production - the issue is, who's going to want it?" he says.